We drove up to see the enlarged and renovated Clark Art Institute in Williamstown recently. It had just reopened after ten years of planning and construction, and we were eager to explore the new Clark Center designed by the Japanese architect Tadao Ando. We were just as excited by the prospect of visiting the many wonderful works in the permanent Clark collection — paintings which had become old friends over the years — that had been out of view during the renovation. The Museum Building which houses the collection had been totally refurbished by the New York architect Annabelle Selldorf. Along with all this, we’d read that the entire 140-acre Clark property had been reconfigured — 1,000 trees planted, woodlands protected, new footpaths installed.

So, it was with a sense of some confusion and disappointment that we drove up the winding drive to the parking lot and saw that nothing much had changed. There was the same lovely rollercoaster of mountains in the distance. And there was the old white marble temple that housed the permanent collection. Yes, there were some low-lying buildings off to the right, but they looked so nondescript and utilitarian we at first mistook them for a maintenance area. It wasn’t until we walked down a long gravel pathway and passed through a glass side entrance which opened up to a stunning view of reflecting pools and mountains that we realized we’d entered the Ando building. It had been built low on purpose, with much of its new exhibit space underground, so as not to interfere with the view of the hills. We’d probably reacted just as the architects had hoped. Nothing has changed: the Clark remains a most happy marriage of art and nature. But everything has been subtly and masterfully improved.

Though the new Clark Center feels a little uninviting and stripped-down with its poured concrete walls, it provides a beautiful backdrop for its first exhibition: a stunning collection of ancient Chinese bronzes called “Cast for Eternity.” The renovated Museum Building, on the other hand, just about waved us in. It’s been reconfigured into welcoming new galleries — large and small — with intimate nooks, richly painted walls, and subtle lighting.

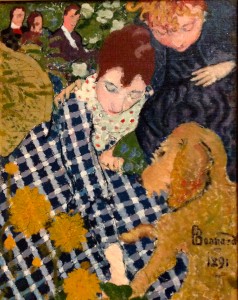

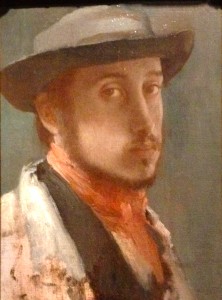

There are lovely new rooms devoted to the Clark’s knock-out collections of Homer and Inness. Our old friends greeted us — but in new places — so each reunion had the thrill of discovery: Bonnard, Millet, Renoir, Monet, Gauguin, Sargent. In a small gallery all its own, Degas’ Little Bronze Dancer gazed pensively at the ceiling. And, in the midst of all these man-made treasures, the newly reconfigured museum didn’t forget to direct the eye outward through its tall, screened windows to the pines, lily pond, and rolling hills beyond.

The Clark has its share of Old Masters, too, including Piero della Francesca, Ghirlandaio, Perugino, Gossaert, Memling, and Breughel.

Here is W. H. Auden’s famous poem about another Breughel painting:

Musée des Beaux Arts About suffering they were never wrong,The Old Masters: how well they understood

Its human position; how it takes place

While someone else is eating or opening a window or

just walking dully along;

How, when the aged are reverently, passionately waiting

For the miraculous birth, there always must be

Children who did not specially want it to happen, skating

On a pond at the edge of the wood:

They never forgot

That even the dreadful martyrdom must run its course

Anyhow in a corner, some untidy spot

Where the dogs go on with their doggy life and the torturer’s horse

Scratches its innocent behind on a tree. In Breughel’s Icarus, for instance: how everything turns away

Quite leisurely from the disaster; the ploughman may

Have heard the splash, the forsaken cry,

But for him it was not an important failure; the sun shone

As it had to on the white legs disappearing into the green

Water; and the expensive delicate ship that must have seen

Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,

Had somewhere to get to and sailed calmly on.

For more Auden poems please visit: https://www.poets.org/poetsorg/poet/w-h-auden